BOSTON COMMON

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

Visited July 15th, 2013

The Emerald Necklace of Boston is a seven- mile chain of parks, walkways, gardens and an arboretum, seamlessly connected together by a series of parkways and open spaces. It was a concept in urban landscape design by American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. My daughter Cara and I visited four of these parks during our short visit when we met in Boston this summer.

Each park has a unique landscape, purpose and history. The Boston Common, America’s oldest public park established in 1634, anchors the northeast end of the chain of parks. It is the historical importance of the Boston Common rather then horticulture features that are prominent. The Common is a history of our nation, and as I found out, a history of my own family.

When I visited Boston I could not escape the history of the early English colonists that sailed the ocean to the New World. Those colonist and other immigrants that followed were on the path that shaped Boston and the founding of our country. When you visit Boston, history will be in the photo lens of our current lives.

The reign of King Charles I, of England (1625-1649) was a time of religious and political turmoil. The Pilgrims and Puritans were judged religious dissenter, often persecuted, stripped of their livelihood or imprisoned. In 1628 a group of Puritan businessmen formed a profit- making venture to the New World, eventually under the name of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and were given a charter, by the king, for a large tract of land in the New World.

A group of colonists left Southampton in April 1630, eventually settling in what is now named Boston. By then company was no longer a trading company for profit but a staunch group of Calvinist Puritans who wanted to purify the Church of England by establishing a city upon the Blue Hills near Boston as an example of how godly people should live. By 1640, the end of 20 year period known as “The Great Migration “over twenty thousand men, women and children had left England to settle under the Massachusetts Bay Colony, with Boston as the economic center of the colony.

When Governor John Winthrop moved this early group of colonist from their original arrival point of Charlestown across the river to Shawmut (Boston), to obtain suitable water for drinking and brewing beer, he found Reverend William Blackstone, (originally from County Durham England), living alone on 487 acres. The Reverend had arrived in 1623 with the first group of European settlers to arrive on the peninsula. After two years his fellow settlers returned to England. He elected to stay, living on Beacon Hill where he gardened and planted the first apple orchard of the New World. Governor Winthrop bought the rights of Blackstone’s land soon after arriving, except 50 acres. By 1634 the Anglican Minister had found the Puritans with their religious intolerance difficult to live with. He sold his remaining acreage to them over a period of time. Moving south where religious freedom was liberal, he re-established his farm, home, garden and apple orchard in an area that eventually became Rhode Island.

The 50 acres then named “The Commonage,” became important public community land for the Puritan’s. Each household had been assessed evenly to buy the land to use as common area for the raising of pigs and pasture for cattle and sheep. The local militia also used it for practicing maneuvers. The citizens passed an ordinance that would prevent the sale or lease of the Common except by a majority vote of the people. It was the first public park owned by the citizens of this country.

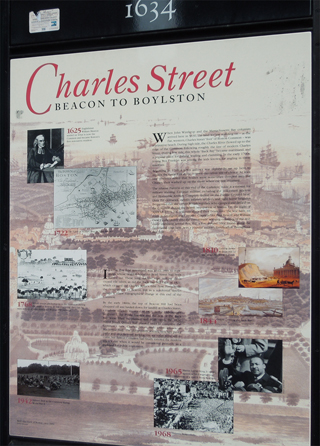

Over the centuries the landscape of the common would change from functional; an open pasture with salt marshes along the river’s tidal edges where Charles Street is today, to a public pleasure ground. A walkways laid out in 1675 was the beginning of change in the physical appearance of the park. Grazing of livestock was eventually banned allowing open lawns. Hundreds of shade trees were planted primarily as alless along malls and paths or in groups near important features. English Elms, their numbers reduced having been cut down by the British occupation forces or declining from age, were replaced by American Elms.

By 1815 Charles Bulfinch, a Boston architect, had built brick row houses on three sides of the park, inhabited by the upper class. With increased traffic and the upscale commercialization of the surrounding area, a decorative cast iron fence was placed around the entire Common with gates to define entrances and exits. The Urban Park Movement of the mid 19th century influenced the addition of fountains, monuments and memorials.

During 1895 the landscape of the Common changed with the construction of the nation’s first subway. The location was controversial but when completed, a subway tunnel ran under the park. With construction of the underground subway, earth and numerous park trees were removed.

Over time the Common did evolve into a park for all people, regardless of social or economic status, race or nationality. Now picnics with family and friends under the canopy of mature deciduous shade trees or a place to walk the dog, shaded from the afternoon sun, provide respite from city life. Amateur musicians gather to provide an impromptu jam session near the frog pond. Numerous wooden benches under the shade trees line pathways; an invitation to sit, reflect, text or read.

Recreation and entertainment for adults and children is an important aspect of the park. The wide expanse of green space provides room for ball fields and tennis courts. Presented under the summer stars, free productions of “Shakespeare on the Common” are performed. When Cara and I entered the park in mid-afternoon a free nine day” Outside the Box” festival of music featuring power pop rock bands to country music was in progress. The Barnstar’s could be seen on a jumbotron screen, their bluegrass music followed us for some distance into the park. I sat in the shade and listened to the end of the concert before continuing our walk further into the park.

Since 1856 audiences have been treated to a variety of free music. Promenade concerts, which were popular in Europe and England at that time, arrived on the Commons played by local bands. In the 20th century musical variety included Judy Garland to a rock concert with a psychedelic light show in conjunction with a peaceful Vietnam anti-war protest. The Boston Symphony celebrated 25 years of classical music under the baton of Seji Ozawa at the Boston Common. Bring your blanket for free lawn seat entertainment.

During the British occupation of the Common, children would slide on sleds on the hillside, sometimes complaining that the British troops interfered with their coasting. By the 1850’s the Common was a popular playground for neighborhood children. Entertainment is still provided for young ones with carousel rides that feature horses, animals, and frogs with teacups for the smallest to sit in. Nearby is a pond nicknamed the Frog Pond, an enclosed concrete lake with a fountain installed to provide water with a 70- foot spray plume. The pond was originally used for watering cattle when it was fed by run off water. At one time the ice on the pond was harvested for local residents.

At the edge of the Frog Pond are two appropriate bronze sculptures. A frog with a fishing pole and a companion frog, possibly reflecting on the fish that got away, were favorites of children who were climbing and hugging them.

The frog pond is a cooling fountain for children and adults. It was afternoon, the temperature in Boston higher then usual that week so Cara and I welcomed a soak of our feet in the pond. In the autumn it is a reflecting pond. By the 1850’s it had become a skating pond in the winter and continues as a skating rink to this day.

The park is not an ornamental garden by design. Shrubs, flowers and ornamental trees are kept to a minimum and usually restricted to the edges of the park and around monuments. Park Department horticulture staff propagates, installs and care for the plants in the Common area as well as the numerous well maintained planters and display beds located near the streets and the Public Garden.

The Boston Parks and Recreation Department focuses on maintaining and caring for the Common with its hundreds of trees within the park and also along the Commonwealth Avenue that links the Boston Common with the Public Garden and Back Bay Fens park.

The Dutch elm disease was a hard lesson in the importance of tree diversity. Visual interest, drought tolerance, spacing and species of trees that tolerate the stress of urban conditions and disease, are considered when tree replacement is required. A schedule is followed for fertilizing, pruning, spraying for disease control and watering newly planted trees. Turf maintenance is also required, especially in the areas that receive heavy foot traffic.

As a public park the Common has been a gathering place for citizens for celebrations, free speech and protests rallies. Demonstrations over the past and current century have played out the stories of peace, turmoil, wars, religion, politics and social concerns. As early as 1713 there were food riots by the hungry poor over the monopoly of grain by merchants. The 20th century saw numerous protests rallies of the Vietnam War. The social and political consciousness of the times has acted out on the grounds of the Common, reflecting not only the city of Boston but also our country.

Ironically, the Puritans that fled religious strife and persecution in England were intolerant of other beliefs. Quakers were despised by the Puritans and by 1656, the Boston Quaker Law was invoked which imprisoned, brutally treated and expelled Quakers from Boston. A law in 1658 passed a death penalty to all Quakers who returned to Boston after having been banished. Mary Dyer, a Quaker preacher exiled from Boston was hanged from a great elm tree in the Common after returning to Boston in 1660.

Margaret Jones was a midwife, herbalist and physician, accused of a “malignant touch.” Governor Winthrop was the judge at the trial and signed her death warrant. She was the first person executed for witchcraft in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. She was hanged from the great elm tree in the Commons in June 1648. Ann Hibbins was hanged from the same great elm tree in 1656, because of unjust, superstitious Puritan laws of witchcraft.

With the expansion of Massachusetts and a new secular political charter in 1692, the puritan political influence largely disappeared. The attitudes associated with it remained for some time but eventually the citizens of Boston became more tolerant of differences. The Puritan ethic of hard work, moral character and the importance of education did continue as part of the Yankee character.

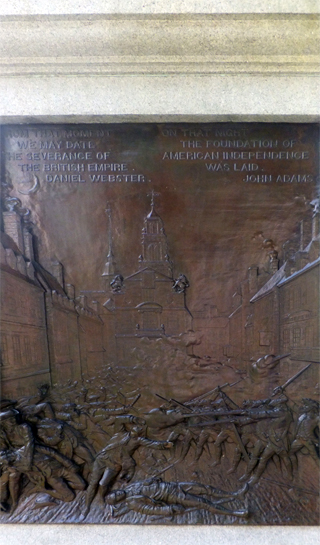

Boston was a leader in the movement to obtain independence from the British. Early political scenes of revolt and celebration were acted out on the Common, leading up to and through the War of Independence. A mass meeting in opposition to the Stamp Act, (the first direct tax in the American colonies), was held on the Common on November 1st, 1765. A boycott of British goods was put in place which in short time severely affected the British merchants. On June 4th, 1766 a celebration of the repeal of the act was held under the Liberty Tree with fireworks, and a “picnic of roast ox, twenty-five barrels of ale, and a hogs-head of rum punch”. The obelisk designed by Paul Revere, decorated with patriotic imagery, was lit with 280 lanterns. It did not survive the night, destroyed by fire before the party ended.

From 1768 till the end of the war in 1776, the British camped on the Common. They used the trees as firewood; cutting down the Liberty Tree but sparing the great elm whose purpose had been to hang pirates, common criminals, witches and religious dissenters. Several years after the war ended George Washington, John Adams and General Lafayette attended a celebration together, of our nation’s independence at the Boston Common.

The 1850’s saw anti-slavery meetings on the grounds of the Common. With the war between the North and the South, Civil War recruitment of free blacks took place in Boston on the Common. Frederick Douglas was involved in the recruitment of the Unions first free black regiment, the Massachusetts 54th, who fought valiantly at the battle of Fort Wagner in South Carolina during July 1863. They were trained and led by Colonel Robert G. Shaw, who was from a privileged white Bostonian whose family were abolitionists. The Colonel was killed in this battle and what the Confederates considered an insult, buried him in a mass grave on the battlefield with his fallen black troops. Two years later in April the Bostonians gathered at the Common to celebrate the fall of the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia. Within the month, citizens would gather on the Common in grief with the news of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

Even though black American’s continued to voluntarily serve in the armed forces in our countries conflicts, a century later after the Emancipation Proclamation there was still a struggle for equality for all. In April of 1965 Martin Luther King, Jr. led a mile long freedom march through Boston and onto the Common calling for accelerated desegregation of housing and schools and for the destruction of the ghetto.

War continued to play a part in the activities taken place on the Boston Common. WWI and WWII saw Victory Gardens planted by citizens to provide food for the general public due to food shortages. The Common gave most of its iron fencing to be used for scrap metal during WWII. End of the war victory celebrations were held on the Common.

After two World Wars there was a call for world peace by religious evangelist and leaders. In April 1950 the young Billy Graham held an outdoor revival at the Common. He stood on the same spot that George Whitefield, the great evangelist of the 18th century had stood 210 years before when leading the Great Awakening in New England. It was gray skies and a rainy day. It was reported that with the singing of “Showers of Blessing” and “Heavenly Sunshine,” the rain stopped and the sun shone briefly, as the Reverend said it would. He outlined five programs for world peace and called for a “National R” to repent of sins.

Oct 1st 1979 saw 400,000 people gather on a rain soaked day to participate in Pope John Paul II first papal mass in North America. His visit was to a city strained by race relations with court ordered school desegregation and a tragic racial shooting 3 days beforehand. The Pope appealed to young American Catholics “to reveal the true meaning of life where hatred, neglect or selfishness threaten to overtake the world.” and “embrace the “option of love” taught by Jesus.

Political unrest of the 60’s and 70’s saw the hippie invasion of the flower children in the summer of 1968 gathering for a Love-In. They cooled off in the Frog Pond, listened to rock bands and found a sense of community they said they could not find anywhere else. A year later Senator George McGovern addressed an anti-war rally with 100,000 peaceful demonstrators gathered on the Common to protest the Vietnam War.

National news draws impromptu crowds to meet at the Common. In May of 2011, the people of Boston gathered there spontaneously to celebrate the news of the death of Osama Bin Laden. The park also provides space for people to rally in support of friends and neighbors. In May 2013, one month after the tragic bombing near the Boston Marathon Finish Line, a gathering was held to celebrate life and heal the wounded with the power of music and dance and to raise money for the victims.

On June 4th, 2013 a sapling Horse Chestnut tree was planted on the Common near the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial. It was a sapling from a 170 year- old tree that had stood outside a secret annex in Amsterdam where Anne Frank and her family hid during WWII. Anne Frank believed that “nature brings solace in all troubles,” and she wrote in her diary of the comfort the tree gave her throughout the seasons while she was in confinement.

A fifteen -year old teenager from Brookline had encouraged the city to apply for one of the eleven saplings that would be awarded to organizations or cities that exhibited the legacy of the Anne Frank’s belief in equality, tolerance, civil rights and social justice.

The Boston Common “hangman’s” elm tree was permanently felled by a winter storm in 1876. Anne Frank’s horse chestnut tree, a symbol of hope, was felled by disease and a windstorm in 2010. Prepared for the inevitable, saplings had been propagated from the tree’s chestnut seeds. Boston qualified for one of the saplings, an appropriate replacement of the old elm to remind us of the importance of continued cooperation and tolerance with all of our fellow citizens.

Cara and I would be leaving Boston the next day, flying out of Logan Airport to our respective homes; she flying back to Manchester England and I to Virginia Beach, Virginia. There were faint footsteps behind us in Boston from many generations past that place my family where we are today.

John Perkins, Sr. was born in Newent, Gloucestershire, England in December 1583, was baptized at the St. John’s Baptist Church in Hillmorton and later married Judith Gater at that church. On December 1st, 1630, John, Judith and their five children boarded the ship Lyon, in Bristol, with 20 passengers on board and two hundred tons of goods. After 68 days of stormy seas, the Lyon anchored at its final destination, Boston.

The Perkins family lived in Boston for two years, with their youngest child Lydia, born in the New World and baptized in 1632 at the First Church of Boston, founded by Governor John Winthrop. John and Judith Perkins were in good standing in the Puritan community as they were both admitted to the church and John took their Oath of Freeman. The Governor founded a new colony at Ipswich (30 miles northeast of Boston) and the Perkins family moved there in 1633. John Perkins was involved in the founding of this early community and was deputy to the General Court in Boston. He was a landowner engaged in agriculture and was also granted an island that is now known as Perkins Island. He was a member of the local militia until he was released due to his age being over sixty. He died in 1654 and Judith shortly after.

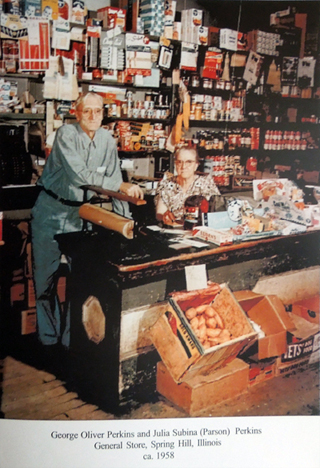

John and Judith Perkins were one of the families of the “Great Migration,” whose future generations included my grandfather, George Oliver Perkins, who as a child was brought from New York to Atkinson, Illinois by his father. George married Julia Parson in 1907. She was a daughter of Swedish immigrants who had met in this country after settling in Galva, Illinois, a town heavily populated by Swedish immigrants in the 1800’s. I remember as a young girl the two- hour family Sunday drives from Geneva, Illinois to the village of Spring Hill, where my mother would visit with her parents. As grandparents often do, they indulged their grandchildren with sweets and Cream Soda (my favorite), from the Spring Hill General Store they owned and operated.

The groups of early English ancestors that migrated to the New World and merged with immigrants that followed have created what has been called the “melting pot” of our country. They formed the foundation of our society. Building on that foundation has continued to this day.

Photos by Deborah McMillin & Cara McMillin

Photo of George & Julia Perkins from “Shared Traditions A Family Album Descendants of Amasa and Lucy (Bullard) Perkins 1795-1999” Author George F. Perkins

References:

Friends of the Public Garden, Boston Common Management Plan 1996

Morgenroth, Lynda. Boston Firsts. Boston: Beacon Press 2006.

Perkins, George A., M.D. The Family of John Perkins of Ipswich, Massachusetts. Salem, MASS, Printed for the Author by the Salem Publishing & Printing Co. 1889

Weesner, Gail & Friends of the Public Garden. Images of America Boston Common. Arcadia Publishing SC. 2005