Travel Connections

Visited June 7th, 2014 with the Lakeland Horticulture Society.

Our noon lunch was in the small town of Kisa at the Cafe' Columbia. Unexpectedly it provided me a chance to reflect on my Swedish heritage with a visit to the Kisa Museum of Emigration. The small collection of Swedish memorabilia on the second floor of Cafe' Columbia tells a story of people who left their native country of Sweden for an opportunity to change their lives in 19th century America. With the limited information I have on my ancestors from Kristianstad and Halland, they may have left Sweden for the mid-west of America for similar reasons and opportunities that the families of Kisa and the surrounding regions did.

In 1846, the building that currently houses the Cafe' Columbia had been a pharmacy. The pharmacy also served as Sweden's first emigration bureau. In May 1845 a small group from Kisa, led by a farmer and master builder Peter Cassel, (who had been influenced by the pharmacist talk of the “Land of Freedom”) sailed from Gothenburg, Sweden to New York, an eight week journey. They settled in the mid-west of the United States and named their Iowa colony New Sweden. The Museum of Emigration is in memory of this group and the people from Östergötland and Northern Småland, (where rural conditions were bleak at that time) who later followed.

These early migrations were due to poor economic conditions as well as religious and political oppression. In the mid 1800's Sweden's population was supported by an agriculture society (vs. an industrial society). There was poverty among the Swedish farmers due to their small farms, poor soil and land mismanagement. A group of 1500 religious nonconformist from Central Sweden settled in Bishop Hill, (Henry County) Illinois from 1846-1850.

During the late 1860's there was famine in Sweden caused by crop failures with too much rain then drought. Mass migration, mainly of farm families, took place from 1867 – 1873. Another large migration to America occurred from 1880 – 1893, due to economic conditions in Sweden. This time it was not only farm families but individuals; young people who were loggers, miners, or factory workers from cities. Emigration halted with World War I in 1914. It then continued after the war until the 1920''s Great Depression in the United States. With improved economic conditions in Sweden after 1920, migration slowed considerably to America.

As I was looking through this museum I was interested in finding any mention of the photos on the walls or newspapers identifying places near my home town of Geneva, Illinois. Geneva has celebrated its Swedish heritage annually (since 1911) in June with a week long celebration of the Midsommar, the Swedish national celebration of the day in mid June without the setting of the sun. When rail lines connected from Chicago to Geneva in 1853, Swedish immigrants (as well as Irish and later Italian) moved to Geneva. By the turn of the century half the population of the town were Swedes. I did find several Swedish newspapers; Svenska Amerikanaren Tribune published in Chicago and a newspaper from nearby Aurora.

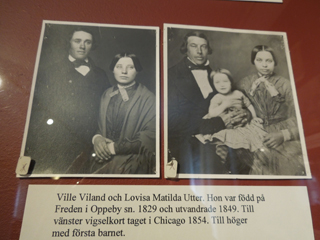

There were collections of letters and black and white faded photos of families that had migrated from Kisa to Illinois and other popular areas; the Mississippi River Valley and the states of Iowa and Pennsylvania. Photos of young faces with names; Carl Gunnar Nylander from Kiska to Aurora, Illinois and his younger brother Gustaf Walfried, to Red Oak, Iowa. Other faces in photographs were identified with final destinations of Chicago, nearby Evanston and eastward across the country to Mount Jewett, Pennsylvania.

Letters written by immigrants of 1846 to their families in Kisa painted a different picture of life then what Peter Cassel had portrayed and promised as the “Land of Canaan.” Johan Fahram wrote that when they reached Iowa and their fellow country man (who had traveled in the original group of 1845), they found illness, lack of money to buy land, and food expensive or inedible. Forty years later there were positive experiences for other immigrants. Nils Blomberg wrote a letter in 1886, from Lindsborg, Kansas, to his in-laws in Kisa that was positive with details of a farm purchase of 320 acres and the ability to buy hogs, cattle and farm implements.

The Homestead Act of 1862 promised 160 acres of undeveloped land outside the original 13 colonies to any who applied for it, under the condition they had not taken up arms against the U.S. Government. Homesteaders paid a small filing fee and were required to complete five years of continuous residence before receiving ownership of the land. An alternative was six months of residency and the purchase of the land from the government for $1.25 per acre.

The Homestead Act instigated a movement of Swedish farmers whether poor, landless or well established, to the upper Midwest and later the Great Plains states. Iowa and Illinois with fertile soil and cheap open land were the preferred states for farmers. Minnesota with a large percentage of the population Swedish, was nicknamed the “Swede State of America.” Chicago and Milwaukee were the favored cities for the young and single Swedish immigrants.

My great grandmother, Ellen Pearson (Feb. 9,1861 – April 30,1942) migrated to America from Valleberga, Kristianstad,(southwest of Stockholm) in 1870 as a young child with her sibling's and parents, John Pearson & Ellen (Anderson) Pearson. The family settled on a farm in Henry County near Galva, Illinois, a Swedish community not far from the Bishop Hill settlement.

My great grandfather, Andrew Paul Parson (Jan. 19th, 1851 – July 22, 1941) from Vapnö, Halland, (on the western coast of Sweden) came to America through Ellis Island – New York in 1876 at the age of 25. He married Ellen Pearson in June of 1881, in Galva, Illinois. Ellen and Andrew had seven sons and two daughters. My grandmother Julia Subina Parson, was the oldest girl born on their farm near Galva on February 13th, 1882.

Julia married George Oliver Perkins May 1907, at the home of her parents with her uncle, Rev. Swan Pearson officiating the ceremony. My mother, Lucille Eleanor, was born in August of 1915 at the family home in Spring Hill, Illinois. Her father was afraid that his red headed daughter would be nicknamed Lucy, which he did not like, so Eleanor was the name my mother was known by throughout her life.

Home to my mother and her three siblings was the Spring Hill General Store which their father built as a combination of business and a residence. General Store was a suitable name for the business as I recall hundreds of items besides groceries on the shelves and stacked on the wood floor, that served the small surrounding communities.

From the Family Album of “Shared Traditions,”my mother Eleanor wrote of the frequent times spent with her maternal grandparents Andrew and Ellen Parson in Geneseo while growing up; helping with housework, running errands, feeding chickens and fixing breakfast of poached eggs, toast and Swedish egg coffee for a boarder when her grandmother was not feeling well. It also gave her a chance to spend time with her cousins who lived in the town.

It was in her grandmother Parson's home in Geneseo that my mother was married to my father Marcell Harry Hall. Their December 6th engagement was shortened to three weeks due to the December 7th 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor and Marcell's immediate decision to enlist in the Coast Guard.

My mother had recalled the family story to me that my grandmother Julia did not start to speak the English language until she was seven years old, possibly at the time when she would have started school. For the adult immigrant in America, their native tongue would remain the standard language at home, church and within their own community to connect socially. The children learned English rapidly when they attended school. Their parents not comfortable with the English language, would learn what was needed to conduct business.

I faintly recall times when I was visiting my grandparents as a young girl, my grandmother would lapse into speaking her parent's native language and dinnertime grace was often spoken in Swedish. My mother also told me that as she was growing up, she would hear her mother Julia converse on the phone with her own mother (Ellen) in Swedish. My mother said that she never learned the language but wished that she would have. At that time the native language between an immigrant mother and first generation daughter would have been a way to connect with their shared heritage.

Lilacs and hollyhocks in my grandmother's yard are also a memory recollected from a summer I spent with them in Spring Hill as a young girl. A lilac bush in my own mother's yard, with deep purple blooms was from a slip taken from one of those bushes.

The stories of Perkins side of my family are well documented starting with John Perkins, Sr. (of Puritan faith) from Newent, Gloucestershire, England. He left with his wife and five children in December of 1630, to escape the political and religious turmoil under King Charles I, to Boston, Massachusetts. He and his wife Judith eventually lived out their lives in nearby Ipswich.

Currently I only have jig saw puzzle pieces of the families from Sweden. My great grandmother Ellen Pearson Parson came to America (1870) as a nine year old child under the protection and guidance of her parents. They chose to settle in the town of Galva named after the seaport Gävle in Sweden. The religious community of Bishop Hill aided in the building of Galva, a community less isolated. Who did the Pearson family follow or why? Was there a religious motive? Little tid-bits of written sentences and photos of the Parson family in my cousin's genealogy book (of the Perkins family) and my trip, gives me the urge to see the completed puzzle of those families. But that takes time.

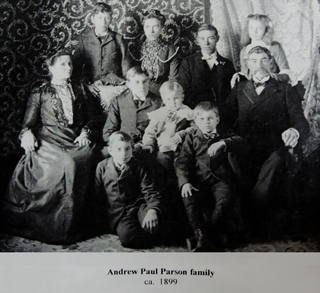

A black and white photo of the Andrew Paul Parson family from ca. 1899 shows the ten posing in their formal Sunday best, the women buttoned up to their chins. By early 1930's the family photo count is twenty nine faces; the women in loose collars and dresses, an indication of the succeeding generation's acceptance of their place in time.

My great grandfather Andrew Paul Parson from Vapnö, Halland came to New York in 1876 at the age of 25. He would have come through Ellis Island. What would that experience have been for him? Was he traveling alone or with siblings or friends? I know a piece of the puzzle that his father, Per Jonsson died when Andrew was seven years old. Were the family farmers and effected by the downturn of crop failures of the mid 1800's plus the death of a parent in 1858? From visiting the Swedish Open Air Museum in Stockholm, the region of Halland is represented with a farmstead of the 1870's.

By the age of 30, Andrew Paul Parson had made his way from New York to the mid west of the country and married in Galva, a farm girl, 20 year old Ellen Pearson. That is where my grandmother Julia's story begins in my families life continuing with my mother, me, my daughter and granddaughter.

The Kisa Museum is an honorable reflection of the local population that remained in Sweden during difficult times. As a community it believed that it was important to memorialize the lives of their neighbors and kinfolk who had taken considerable risks for a new life in 19th century America.

Whether memories of our ancestors lives and activities are collected in a museum, a book of text and or photos, video, recorded words or digital media, our shared recollections are an important bond within our families and a connection to our heritage.

As I flew in to Arlanda airport near Stockholm earlier that week, I observed clearly an early morning expansive aerial view of lakes, large expanses of forest and farmsteads surrounded by large clusters of protective conifers. I felt an intense recognition of the country and a connection to the past and my family.

Family recollections are in memory of my mother Eleanor Hill and her life August 18th, 1915 to August 2nd, 2014, with a wish that I would have had additional time to have shared more of my travel and garden stories of my trip to Sweden with her.

Photo Credits

Photos taken in the museum by Deborah Ellen McMillin

Photos of Parson family from "Shared Traditions – A Family Album" compiled and published by George F. Perkins, Normal, Illinois, 1999.

Front Row: Left to Right – Phillip LeRoy Parson, Earl Rueben Parson.

Middle Row: Ellen (Pearson) Parson, George Nathaniel Parson, Walter Otto Parson, Andrew Paul Parson.

Back Row: John Edwin Parson, Julia Subina Parson, Paul Arthur Parson, Mabel Idella Parson.

Julia & George Perkins wedding photo from "Shared Traditions – A Family Album" compiled and published by George F. Perkins, Normal, Illinois, 1999.

Photo of Lucille Eleanor Elizabeth Perkins Hall and Marcell Hary Hall from D. McMillin's photo collection – ca 1942.

Photo of Halland Farmstead Open Air Museum at Stockholm by Deborah Ellen McMillin.

Photo of Cara Lynn McMillin & Eleanor Hill & Deborah Ellen McMillin (1998) by Tom Maloney.

References

"Personal Family History – Shared Traditions – A Family Album" compiled and published by George F. Perkins, Normal, Illinois, 1999.

http://www.kulturarvostergotland.se/Article.aspx

http://www.genevahistorymuseum.org/

http://www.lib.niu.edu/search.html

http://www.everyculture.com/multi/Sr-Z/Swedish-Americans.html